In Mountain Meadows, an immensely satisfying play receiving an excellent premiere in a Pygmalion Theatre Company production, playwright Debora Threedy frames Juanita Brooks, the Utah historian who wrote the first comprehensive book about the darkest event in the state’s Mormon pioneer history, as a moral superhero.

But even Nita (as the character is known in the play) is not above complicated human emotions, in Threedy’s fictional narrative treatment. In a scene set in the middle 1940s, she is in a sullen mood, as she pulls pieces from a large basket of clothes for ironing. Reen (who is actually author Maurine Whipple and is known for The Giant Joshua, one of the most widely known Mormon fiction books at the time, and who was once a student of Brooks) sits in the kitchen, flipping through a magazine. Nita is down because she did not receive a research grant to assist her in completing the manuscript about the Mountain Meadows massacre. Reen tries to downplay the news, even as Nita reminds Reen that when she received her grant, she mentioned how it saved her life.

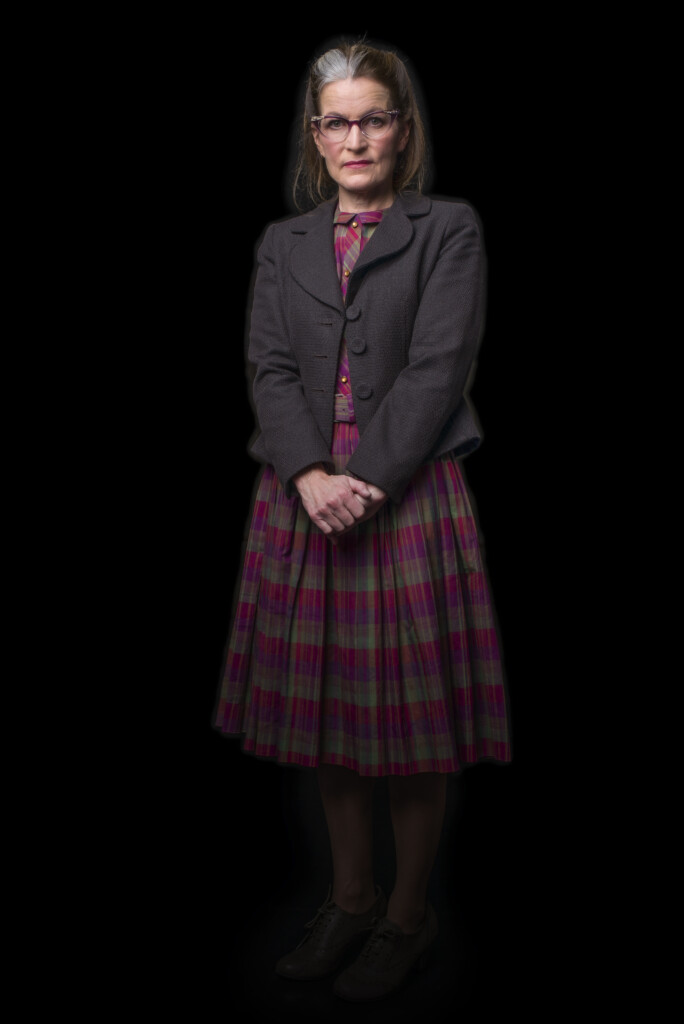

Portraying Nita, actor Stephanie Howell is convincing, demonstrating how her character is trying her best to drop subtle hints that Reen (played by Tiffani DiGregorio) should leave and perhaps visit another day: “I wish I could just sit and chat with you, but I really need to get this done.” Reen is oblivious: “I’m here now and we can talk while you work. I don’t think you should write a history anyway. They’re a little dry. You should take the story and write it as a historical novel!”

The exchange that follows is telling. Reen suggests Nita should write it as historical fiction but Nita is unmoved: “I like the structure facts provide. I’m not very good at plotting a story, but with history, I don’t have to, the story is already there.” Reen suggests that the best way to bring the story to life is to “put a little make-up on its face, and tie a pretty scarf around its neck.” She thanks Nita for helping her with her novel (The Giant Joshua), who shared details and anecdotes to flesh out the story.

But, Reen also wants Nita’s assistance again. “I’m working on this travelogue-y thing about Utah, and all the news-worthy things that have happened in the state, and I want to include something on the Mountain Meadows Massacre, because, well, you know, it’s juicy and exciting. People are fascinated by carnage, don’t you think?” she says.

Nita steels herself as she puts down the iron. Under no circumstances will she offer any research details about Mountain Meadows, remembering how Reen “garbled” historical facts that she shared when her former student was writing her novel. Reen thinks Nita will never publish anything about the massacre for fears of being excommunicated from the church or being branded as an apostate. Their exchange mushrooms into an argument with Reen storming out, proclaiming that she will never ask Nita for anything else again. The scene ends with Nita looking at the iron, as she says, “I knew this was going to be too subtle for Reen.”

Threedy does a formidable job in her script about a devout Mormon who was a teacher, mother and housewife but also a dedicated historian committed to the highest standards of accuracy and truth finding in her craft. Brooks never shied away from the pointed counsel of church authorities who thought it would be better to let the history of the massacre rest without any further disturbance. Likewise, the entire cast in the Pygmalion Theatre Company production, directed by Morag Shepherd, convincingly convey the tremendous emotional currents driving the epiphanies of conscience which propel the narrative arc.

As mentioned in an earlier preview at The Utah Review, in 1950, when it was published, Brooks wrote the most comprehensive book-length history about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ involvement in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. A decade after Mormons arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, a wagon train of 127 immigrants from Missouri and Arkansas were slaughtered in southern Utah by Mormon zealots. The only ones spared were small children. Only one man, John D. Lee, was ever tried for the crime. The jury did not reach a unanimous verdict in his first trial, but when he was retried he was convicted and executed. The story was that Lee had urged the Paiutes to join him in the massacre. To this day, the church continues to obstruct the complete details from being ascertained.

It is an event that anyone who has even lived for a short time in Utah has heard of either directly or indirectly. Indeed, the cast’s exceptionally credible performances are explained in part by the fact that every actor has had at least some connection to Mormons and their history, either directly or indirectly. And, many are descendants of families who were among the earliest settlers in Utah. Joining Howell and DiGregorio in the cast are Matthew Ivan Bennett, David Hanson, Carlie Young and Daisy Blake.

Likewise, Threedy sets up a sensitively drawn boundary between historical fact and the fictional frame which she has positioned so that the expectations of both are preserved even as they are melded for theatrical impact. That also is beautifully conveyed by the stage set design by Allen Smith, with platforms of desert grasses evoking the sense of place in the area near where the massacre occurred.

The production clips along, effortlessly moving back and forth across different timelines in the play, including one spanning barely a decade in the 1800s when Miranda, a child who was spared in the massacre, discovers her family’s involvement. The other covers three decades with Nita persevering as a historian working to verify and piece together the puzzle which comprises the story of the massacre. The narrative braids which Threedy crafted work well and are lucid at every beat.

Plainly, the depth of the performances truly comes through in what unquestionably is a high mark of excellence in Pygmalion Theatre Company’s record of producing original works by Utah women playwrights, in particular.

Performances continue through March 4 (Thursdays and Fridays at 7:30 p.m., Saturdays at 4 p.m. and Sundays at 2 p.m). For tickets and more information, see the Pygmalion